|

Eward Zwick

Photo by Takashi Seida - © 2015 - Bleecker Street

|

FM Chris Chase recently interviewed Ed Zwick,

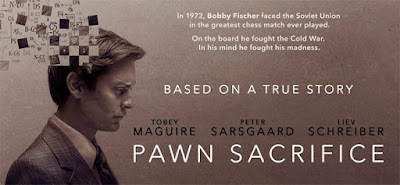

director of "Pawn Sacrifice,"

which opens in Boston this weekend.

Interview with Ed Zwick for the movie

“Pawn Sacrifice” (9/15/15)

Zwick: Hello?

Chris Chase: Hi,

Chris Chase here.

Zwick: Hi

CC: Hi, how are

you?

Zwick: Fine

thanks, how you doing?

CC: Great thank

you. I appreciate your taking the time.

Zwick: Good.

CC: To give you

some background about myself, I’ve been playing chess since 8th

grade.

Zwick: Okay.

CC: I grew up

with Bobby Fischer.

Zwick: Oh my

goodness.

CC: I wanted to

be Bobby Fischer. And so…

Zwick: When you

say grew up with him—did you grow up knowing

him? Or just… as a contemporary?

CC: As a

contemporary.

Zwick: Ah! Okay.

That makes 2 of us.

(Laughter)

CC: So I was

wondering, you know, I watched every game of the match, channel 13 in New York,

broadcast and channel 2 here in Boston picked up every game of the match. It

was the highlight of my 8th grade. And I was wondering, what brought

you to Bobby Fischer and chess? After all these years? I’ve looked at your IMDB…

Zwick: Well, I

mean, yeah I was a little bit older than you—I was in college, in the dorm. I

had played as a kid. I wouldn’t say passionately, but I played a bunch. And,

you know I guess, I was very attuned in addition to chess to the political

landscape—

CC: Okay.

Zwick: It was the

time of SALT II, and because I’m a little bit younger than you, I was actually maybe

in 8th grade or even a little bit younger than that when we were

doing duck and cover and you know my friends and I built bomb shelters and so,

my awareness of the Cold War, and my interest in it was pretty strong. So—to

then see these two men, this young kid, and go out there as a representative of

their respective ideologies—certainly captured my imagination then. But, like many things, and by the

way other movies I’ve made, I’d also read the story of Robert Gould Shaw when I

was at Harvard, and didn’t make the movie about it for twenty years later, so

these things, they reside in your imagination some place and then something

sparks them. In this case, Steve Knight, was a guy, a screenwriter I’d worked

with before, and Tobey Maguire, who was someone I knew because I’d made a movie

with his best friend, Leonardo DiCaprio, were involved in this project that I’d

heard about—through Steve, and through Tobey, and for all I knew, that they

were already to talking to David Fincher, to do it. Only, David Fincher decided

to do something else, and I got a call, from everyone saying would I be

interested in joining them? And the answer was an unequivocal yes.

CC: Huh. No, I

understand that movie was in—I don’t know if production hell is quite the word

for it—but a long time coming.

Zwick: The

financing was. I mean, it was financing hell. I mean, yes, there were two other

writers, and then Steve wrote it, and then getting the financing and all of us

working together on script was a long process, and it finally, you know, found

its way.

CC: I understand

Tobey Maguire’s production company had 10 years involved in this? I want to

make—

Zwick: Yeah, I

think that’s true.

CC: And what do

you think Tobey’s motivation for this—for spending so much time on this?

Zwick: Uh, it’s

hard to find a movie that really interests you ever as an actor or filmmaker.

When you find one that has your imagination, you stick with it, I mean—

CC: Right.

Zwick: In my experience, Shakespeare in Love took, nine years, and—

CC: Really?

Zwick: Traffic

took six, yeah. And Legend of the Fall took 7, and this is something that we’re

all, unhappily resigned to as part of what our lives are like, and you often

work on several things at once, waiting for one of them to sort of become real.

CC: Did you ever,

I was trying to think earlier about who’s surviving from that, and I could only

come up with two names. And one’s Boris Spassky, and he’s living in Moscow, and

I believe, early stage Alzheimer’s.

Zwick: He was not

someone we could talk to, and actually, Father Lombardy is alive—

CC: Yes, he just

put out a game collection. A book recently, which I have. Bill Lombardy is no

longer a priest, he put out a game collection, a book.

Zwick: Yes, I

heard that, and by the way, we spent a lot of time talking to Paul Marshall’s

widow. She was lovely. Paul Marshall died about 3 years ago, but his widow was

enormously helpful and forthcoming. I met other people that knew Bobby, and

Saidy, and others. And Tobey went out of his way to meet people who’d known

him. And there’s a lot been written, and Liz Garbus made a wonderful

documentary.

CC: Right.

Zwick: And there

are the speculative psycho biographies, and there are the things that Bobby

himself wrote and his interviews, and its not like there was any lack of

material to try to draw upon, but at the end of the day, a film is finally a

leap of imagination. It’s not a documentary.

CC: Right. So

there’s no particular one source document for the movie.

Zwick: Not one.

There were so many.

CC: Right. It’s a

very good looking movie. I saw the screening here in Boston last week; it’s a

handsome movie.

Zwick: Well,

that’s nice. We didn’t have a lot of movie, but Brad Young is really one of the

rockstars of his day as a cinematographer, and we had a great group of people

in Montreal. It’s a very vibrant film community there, and they’re used to

making do with very little. And so, we did our best.

CC: Well, you

certainly got your money’s worth, because it’s a very good looking movie. I was

very impressed. And you actually did some filming in Reykjavik? In Iceland?

Zwick: Oh, we

went to Reykjavik for about two days—it’s all we could afford—for about 2 and a

half days. Actually, we arrived and started shooting at night, and went through

the day. And then shot the next day and night. And then we flew—we had 2 days

in Los Angeles at the end I did the pickup crew to get those shots at the beach

and at the Hilton.

CC: I was

surprised. I was thinking much higher budget, based upon…

Zwick: Well, the

reality, you talk about net and gross, because you try to get tax rebates. We

had about 19 million dollars to make the movie, really.

CC: That’s all?

Zwick: That’s

all.

CC: That’s

amazing. You all did an amazing job on that then, because it looks much more

expensive than that. You have, I think A-list stars on it.

Zwick: Everybody on the movie liked it. Well,

every movie an actor loves, so using that phrase is a bit clichéd, but people

did this because they liked the material and they wanted to do it, and nobody

was doing it for the money.

CC: Well, that’s

good. I’m very amazed by that. I had another question. Most of you movies are

sort of what I call earthy. But this movie is very intellectual, in a sense.

How do you, as a filmmaker, how do you handle that? In A Beautiful Mind, they

had some color things with numbers flashing across the screen, and I’ve found

it always hard when people try to represent chess in movies. That seemed to me

a challenge for you.

Zwick: It was. I

knew that it would never be possible to teach the audience chess. I could only

hope that those who knew it would understand that we had some sense of what we were

doing, with other errors hopefully forgivable, or compressions, or omissions,

or oversimplifications because when you’re in a world of film, everything is

necessarily reductive, and so things stand in for other things, almost like

poetry—this means this, this, and this. That being said, I believe that there

was the ability to do something that would be accessible on an emotional level,

or maybe better said, on a subjective level. And I think what you’re maybe

suggesting is this is the first movie that I’ve done that is more of a

character study, and that dominates over the historical context, or even the

plot context. It is deeply introspective in that way. Trying to capture his

subjective experience. And I think that was based on things Bobby had written himself,

when he said that Chess is the domination of one personality by another, or a

book that I read, which you might know, many years ago, that John McPhee wrote,

called Levels of the Game, and he was writing about a Tennis Match between

Arthur Ashe and Clark Graebner, in 1968 or so, in which finally, his thesis

about who won was about mental toughness. And I tried to say there was a way to

juxtapose this internal experience with a larger political context in which it

took place, and to even suggest that there was some kind of spill some kind of

resonance between the two. Because Bobby Fischer, if you think about it, was

really the very beginning International media culture—how someone who was

unknown could suddenly become a household name within weeks. And Bobby Fischer

was the least prepared person for that—

CC: of anybody.

Chess players are like that too, although now it’s different, with Magnus

Carlsen being a fashion model.

Zwick: Although,

I met Magnus actually just the other day.

CC: Really?

Zwick: We saw a

demonstration in which he played four players, he played blindfolded. Four

players at random played against him, and he had a clock, and he took them all

each within 10 minutes of his time. It was really a remarkable moment.

CC: There’s a

fellow in Las Vegas who’s a Grandmaster, and he’s trying to set the record for

blindfold simultaneous of 58 boards.

Zwick: Oh.

CC: It’s that

much. He came here and played 10 boards at once, at the Waltham Chess Club in

Waltham, MA. He’s working hard on that. He’s going to play 50 boards in October

at a Mensa meeting in Chicago.

Zwick: In any

case, he is a sociable person, but you can also see that there seem to be

certain social anxieties that anyone who becomes that sort of reluctant media

star has. I sensed a little bit of that.

CC: In Magnus?

Probably?

Zwick: Just a

bit, yeah.

CC: Bobby

certainly had that. Bobby was just—he’d be very happy on a run by himself with

someone else playing.

Zwick: Yeah, and

that’s the point, that someone like Magnus, or today, people who are

magnificent Olympic swimmers, or people who are even ballerinas, they do have

some opportunity to develop other aspects of their personality or to be

socialized, and you have the feeling that really, he was so involved, from such

a young age, and that chess became such a refuge to him, and devoted himself,

hour after hour, day after day, year after year, to this extraordinarily

draining mental exercise.

CC: It’s a very

hard game. And one thing about Bobby, and most chess players of his era, was

that they had this artist mentality, because there was no money in chess. No

social standing.

Zwick: Although

Kasparov and Magnus both said that, in fact, even in the midst of all of his

demands, you know, he would make 20 demands, and five of them became so

important to legitimize and professionalize chess that, in fact, it was a

remarkable way in which the game did gain stature and respect by virtue of what

he did.

CC: That’s true.

His demands, seemed unreasonable at the time, but actually were very

reasonable, in effect. When he forfeited the championship, he had 3 or 4

demands, which they wouldn’t meet, and all 3 or 4 of them are quite reasonable.

Not the demands of a crazy person. Very reasonable. But the Russians have

always controlled, more or less, the International chess organization. So they

weren’t going to agree to anything. Not for him. At that time. A couple of

other questions. My understanding is that you’re Jewish?

Zwick: I am

Jewish, yes.

CC: I was

wondering how you handled Bobby’s, personally and cinematically, his virulent

anti-Semitism.

Zwick: What can I

say? I know a little bit about what it was to be those Jewish communists in New

York in that period, and to be a red diaper baby. I was not, although I’ve

known many people who were. I’m very interested in what the currency is of that

kind of madness as it declines. I have anecdotal experience with people who’ve

had breaks. And it was very interesting to me in both of those cases, other

cases, in which they chose something regressive as the currency of what they

would focus on, obsess about, be delusional about. Something from childhood.

Something unexpected. In this case, the idea that he would seize on

surveillance, but also his Jewishness, was not surprising to me.

CC: Really?

Zwick: Yeah. We

also know that anti-Semitic self-loathing is something that people think about

who are not having mental health issues. And the idea that there could be some.

Now again, I’m venturing out way past my area here. I’m not a mental health

professional, I’m a writer, and I’m not a physician, I’m a poet. This all just

the kind of speculation that one makes. But as far as the Jewishness went too,

there was great ambivalence toward one’s Jewishness even among the American

Communist Party.

CC: Right. We’re

just all puzzled by it. Most chess players will discuss that, and they’re really

quite puzzled by how Bobby could be so anti-Semitic and yet be Jewish himself.

Zwick: Yeah. And

we didn’t even get to, because it just didn’t seem to be what the point of the

movie was, where he got to by the end. I also did try to talk a little bit in

the movie about the world wide church of god and that fascination that he had

with that really nutty voice too.

CC: When he spent

the night in the Pasadena jail, he put out a pamphlet.

Zwick: Exactly, I

know.

CC: He was

arrested and stripped down, and beaten, and all these terrible things, which

have to be fantasy. I would think they would be fantasy.

Zwick: I know.

CC: Going into

this, what did you think of Boris Spassky?

Zwick: My

impression was that Boris Spassky was quite a like a wonderful sportsman. That

he had a great sense of the game and the sort of the honor of the game. I know

that he was not an ideologue. I know that as soon as the Soviet Union broke up

that he moved to Paris. I know that he probably stayed and didn’t defect

because his wife and children were there during this time. And the fact that he

then developed this peculiar friendship with Fischer for the next years that

followed I think spoke enormously well of him.

CC: Right. No, he

was actually friends before that. He actually recommended—

Zwick: He and

Fischer were friends.

CC: Yes. They

went on a grand tour of South American Chess Tournaments somewhere in the 50s. And

I remember, the one thing I remember is that Bobby used to come to the board

with blue jeans and t-shirts on, looking like a teenager. And Boris recommended

that, why don’t you look better? Why don’t you dress better? And he started

wearing suits.

Zwick: I love

that, because he ended up being quite a dresser. That was one of his great trademarks.

CC: That’s right,

and that basically comes from a comment that Spassky made to him—a friendly

comment made to him.

Zwick: Huh. Well,

boy, you certainly have immersed yourself in all of the Fischeriana.

CC: As I said, I

grew up with, you know, for or better or for worse, right? I mean, after 75’

though, he disappeared completely. He sort of broke our hearts. I think it’s a

great American chess tragedy.

Zwick: Maybe

really just an American tragedy and not just a chess tragedy.

CC: That’s true.

One last question, if I could. You mentioned that Paul Marshall, actually a

fine performance, one of the strongest performances in the movie, I think, by

Michael Stuhlbarg.

Zwick: Yeah,

Michael Stuhlbarg.

CC: You mention

the fact, you imply that he might be CIA, or a government agent.

Zwick: Well, what

I imply, at least, what I look at, at that period of time, if you think about

1970, 1971, and what you know about the connections between the White House and

business, and whether it was Bebe Rabozo, or whether it was money in a slush

fund that ended up dirty tricks, or Watergate, or any of these things, there

was money, and the actual tracing—there wasn’t nearly the same kind of scrutiny

and/or ways in which money was traced. And the fact that they may have funneled

money to Bobby, so as to help him represent, even before that English guy raised the purse, you know,

heightened the purse, I was led to believe, and I think it was Dotty Marshall

who even suggested to us that, yeah, there was help given. I mean, look at all

of the things that were talked about in terms of some of our athletes even

around that time or later, you know, it would not surprise me at all, that

there would be some kind of assistance.

CC: Okay, so that

was the point you were trying to get across.

Zwick: Yeah, it’s

like we said, Bobby wants limos, he gets limos. I’m not suggesting that there

was a great scandal about it, but I—the anticommunism of a certain group of

people, including in the Nixon administration was pretty strong.

CC: Right.

Zwick: Here was

an opportunity to give the Soviets a bloody nose. I think Nixon did have a TV

put in the White House, and Kissinger did call them. These are the facts.

CC: Actually,

where did you get the fact about Nixon having a TV in the oval office?

Zwick: Uhh,

forgive me, I don’t remember.

CC: Because I

mentioned to a couple of people, and they couldn’t remember it.

No comments:

Post a Comment